The Handbasket Thing (Conclusion -2)

I submit that an Animal House/Porky’s minded Jim Kirk could not become Captain Kirk.I read an interesting book recently —

Far be it from me to defend an old TV show, but why take the concept from bad to worse? I’d like to challenge everyone here to aim higher.

One thing the original Star Trek series had, that is all but forgotten now, was a sense of the more noble qualities like fidelity, perseverance, courage, character in the face of adversity, and self sacrifice. On the Enterprise men were men, and women were feminine. And they were explorers.

A week or two ago B questioned the moral obligations of the writer to the reader. Maybe the answer lies in whether the writer wants to make a difference for the better. Maybe it depends on the kind of legacy the writer wants to leave.

That's a redundancy. I rarely read uninteresting books. If the author has not in the first chapter or ten pages or so made a compelling case for my finishing the book, I generally put it aside and forget it. After all, it's not as if there's a shortage of books waiting to be read.

But I digress.

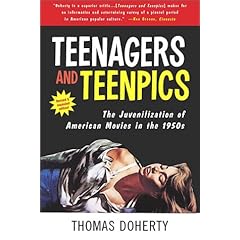

I read this book recently: Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s, by Thomas Doherty. No, not that Tom Doherty, the one who founded Tor Books; the other Thomas Doherty, the one who teaches humanities at Boston University.

I read this book recently: Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s, by Thomas Doherty. No, not that Tom Doherty, the one who founded Tor Books; the other Thomas Doherty, the one who teaches humanities at Boston University.Other Doherty's thing is film, and this book focuses specifically on American cinema in the 1950s, but in his thesis there are hints at a larger lesson. The main thrust of his argument is that before World War II, American pop culture was essentially a monoculture. There were subcultures, true, mostly ethnic in nature, but these were generally small, regional, and on the largest issues still in conformance with the generally accepted social norms: i.e., that men who lived by violence usually died by violence; that adultery was bad; that women who lived outside the accepted sexual norms often came to bad ends, usually via venereal disease or unwed pregnancy; that authority figures generally knew what they were doing or at least meant well; and that growing up poor, illiterate, and fatherless was a terrible handicap to be overcome, not a lifestyle to be celebrated. Certainly sex and violence were present in popular entertainment, but there was a moral dimension as well. Moll Flanders may have been a prostitute, a thief, and a con-artist, but she repented and changed her ways, and this is what saved her. The scandal of a book like Lady Chatterly's Lover was not so much the clumsily pornographic sex; it was that Lady Chatterly neither repented of nor suffered from her adulterous affair.

There were cracks in the façade, of course. For an entire generation of English-language writers, God died in the muddy trenches of The Great War, but the resulting ideas — especially those about hypocrisy, irony, nihilism, cynicism, and the competence and good intentions of authority figures — did not begin to percolate into the mainstream until after 1929.

The tectonic shift that fractured this Pangaea of popular culture began to rumble in the 1940s and struck full-force in the 1950s. Partly it was technological: after the war, television appeared, and in very short order consuming entertainment went from being a social event done with friends or family downtown to being a private activity engaged in behind closed curtains at home. Partly it was economic: after the war there were thousands of Army- and Navy-trained cinematographers on the streets looking for work, and a surprising amount of high-quality surplus equipment and film-stock on the market. Mostly it was demographic: the 1940s saw the beginnings of a Baby Boom (you may have heard of it), and by the 1950s the first Baby Boomers were beginning to enter their teenage years.

The paradigm shift was sudden and very dramatic. Before the 1950s, there was children's entertainment and there was entertainment for adults, and a reasonable person could tell the difference. Moreover, before the 1950s, teenagers were expected in the normal course of life to at some point to give up the things of childhood and become functional and responsible adults.

Sometime in the early 1950s, though, some unsung genius in Hollywood stumbled onto a new truth: that the Baby Boom teenagers had their own cars, their own money, their own tastes, and no longer depended on their parents for guidance, or even permission. Most importantly, in this new reality, it was possible to make literally mountains of money by cranking out entertainment products that catered to the tastes, conceits, prejudices, and fantasies of these often affluent and frequently spectacularly self-absorbed teens.

Doherty marks the transition point as being 1955, and the seminal event as being the film Blackboard Jungle. In its time this movie was alternately praised for its "gritty realism" and widely accused of promoting urban gang violence, and its main musical theme, a rather pedestrian slab of mock-rockabilly by Bill Haley and The Comets called "Rock Around The Clock," went on to become an anthemic #1 hit single and sell more than 25 million copies.

Whatever their other virtues or flaws, though, Doherty's point is that Blackboard Jungle and "Rock Around The Clock" were the first really hugely successful attempts by the film and music industries to package and market adolescent rebellion to Baby Boomer teens. And our culture is still reverberating from the impact.

To be continued...